(V.M. Syam Kumar, Advocate, High Court of Kerala)

Every

branch of law has its own share of land mark judgments. They are important mile

stones in the evolution of law. Teachers teach them with emphasis and students

study them earnestly. The study of law of tort is thus incomplete without

reading Donogue V. Stevenson. Similarly, Constitutional law

cannot be taught excluding Marbury v.

Madison. Students of Contract law cannot ignore Carllil v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. and Company law demands deep

acquaintance with Salomon v. A. Salomon

& Co. They are cases which are to be chewed, eaten and digested at the

law school. Maritime law too has its own fair share of land marks to offer. The

House of Lords decision in MV Indian

Grace is one among them.

Whatever

cult status these legal land marks may have had at the law school, they are

soon forgotten when we are out of the law school. The name of the case may

still ring a bell, but the specifics may no longer be retained. Practice as a

lawyer throws up other important legal norms of contemporary relevance to be

remembered and the earlier land marks gradually fade from memory. They have

only ‘academic relevance’ now.

Further as most of these land marks are antiques from by gone times, they are

seldom cited as authority of value since much water might have flown

thereafter. At the best, a passing

reference may be made to them in a case of comparable facts or legal issues.

That too only before a so called ‘academically

inclined judge’, whose creed is fast vanishing.

Never

in our wildest dreams do we expect to be part of the said land mark judgments

or to get an opportunity to argue them out afresh. Who would expect to get to

argue Donoghue V. Stevenson in the court room all over

again as a lawyer for one of the

parties to the dispute. We presume,

and rightly so that the ginger beer consumed

by Mrs. Donoghue would have long been

digested with or without the snail and the smoke balls that Mrs Louisa

Elizabeth Carlill had purchased to cure her aliment of flu would not survive

beyond the date of the judgment in Carlill

v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Co.

Similarly,

while at law school I had like all my class mates expected that MV Indian Grace would have completed her

voyage long back and all legal issues involving her cargo of shells and

cartridges would have been laid to rest with the House of Lords decision. We

presumed that the shells and cartridges carried on board MV Indian Grace for use in the Bofors howitzer guns acquired by

Indian armed forces would all have been expended on our enemies at the

borders. Dr. A.M. Varkey our professor

at Law school had made each of us read through the MV Indian Grace decision over and over again to impress upon the

nuances of admiralty jurisdiction and the vexing issues concerning in rem and in personam actions involved therein. Like the rest, I expected MV Indian Grace to be relevant only for

what is contained in the House of Lords decision. I was utterly wrong in presuming so.

By

some strange twist of fate, after enrolling as a lawyer I had to be party to

the final legal voyage of MV Indian Grace and was called upon to

defend her based on those very same issues and facts about her and her cargo

which I had learned by heart at the law school.

It

all started one day with a dusty and shabby case bundle which I saw resting on

my table upon my return from the court. I had just shifted my practice to Kochi

and had joined the law firm Southern Law Chambers. I had had a prior stint as a

junior to the legendary maritime lawyer S. Venkiteswaran in the Admiralty Court

of Bombay. After my return I had just started attending the firm’s work and the

bundle had been placed on my table at the instructions of the Senior Partner.

It carried a note that I shall study the file and be prepared to argue the case

as and when it comes up for hearing. It was clear that the green horn from

Bombay with a Masters degree in Maritime law and bearing the tag of being the

junior to the best maritime lawyer in India was being put to test. I carried

the file home for study and slept over. Early morning next day, I proceeded to

open it up and the contents revealed a suit filed by Government of India to

recover some amounts from a company by the name M/s. India Steam Ship Company

purportedly towards damages for the alleged short landing of some military

equipment. The suit had been decreed and the defendant shipping company had

come up in appeal before the High Court of Kerala challenging the judgment and

decree of the Subordinate Judge, Cochin. The plaint disclosed the name of the

vessel in which the cargo was carried and owned by the defendant M/s. India

Steam Ship Company as MV Indian Grace.

The

initial feeling that possessed me on reading the name MV Indian Grace was more that of a cheeky little surprise. What

kind of coincidence could it be that there is another vessel bearing the same

name as the legendary Indian Grace. I

proceeded find out by reading through the dusty and worn out bunch of documents

in the bundle. There was nothing in them connecting it to the House of Lords

decision in the classic English case of MV

Indian Grace. It spoke nothing about action in rem or action in personam

and it related only to a simple suit for damages filed in the Subordinate

judge’s court of Cochin. So this could

never possibly be the same ship MV Indian

Grace about which every student of maritime law across the world is taught.

Later

that day, I consulted my colleagues at the firm and asked them about the dirty

bundle. All that they knew about it was that it is an old file that had been

lying there since years and that the every time the matter came up for hearing,

it was being adjourned by the Government Pleader. None of them knew about MV Indian Grace and the strange

similarity that the subject vessel in the file bore to the land mark decision.

As

I had by then forgotten the specifics of the

House of Lords judgment in MV Indian

Grace, I decided to consult Christopher Hill the acclaimed author of

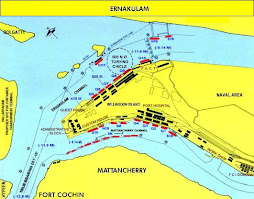

“Maritime Law”. What I read left me startled. This is what he had to say on MV Indian Grace:

“A case on the point is the Indian Grace

(1998)1 Lloyd’s Rep. 1 HL. The plaintiff cargo owners brought proceedings

against the owners in the Court of Cochin and then brought an action in rem in

England. Subsequently judgment was delivered in Cochin. In due course owners

submitted to the jurisdiction of the Admiralty Court. The plaintiffs threatened

to arrest the vessel and security was provided. The issue was whether the

England action in rem was ‘between the same parties or then privies’ within the

meaning of sec. 34 as the action in which the plaintiffs obtained judgment in

Cochin. When English action in rem was launched no judgment in personam in

Cochin had yet been obtained; .....The English action was struck off. The case

has been criticised by leading authors.”

So

the bundle in my hand was the appeal from the judgment of the Subordinate

Judge’s court Cochin, which had been relied on by the House of Lords to strike

off the English action. Issues in MV

Indian Grace were thus still alive and kicking. The thrill that I

experienced cannot be described in words. Here I had that once in a life time

opportunity of pursuing further a case of classic genre. I set to task at once.

I

rushed to the only place in the entire State which then had the Lloyd’s Law

Reports, the most authoritative law reports on shipping cases from across the

common law world, viz., the library of old High Court of Kerala at the Ram

Mohan Palace. I knew from my daily visits, the exact place where the Lloyd’s

Law Reports were stacked. No one came to that part of the library and the

Lloyd’s Law Reports starting from 1918 to date remained neatly stacked in

undisturbed slumber since ages. The book rack had by its side a window and one

could stack books on its side, sit next to it and read. There was no electric

fan over head but the gentle breeze that comes in once in a while through the

window made reading there a pleasurable experience. For weeks, I spent all my

afternoons perched on that window reading through the reports, ofcourse

starting with the House Lords decision in Indian

Grace.

The

appeal to be argued before the High Court of Kerala though arising out of same

facts was different from the legal issues considered by the House of Lords.

Factual aspects as brought out during trial at Cochin assumed more relevance in

the appeal. Comparing and confirming the factual observations in the judgment

of the House Lords with the documents available in my bundle became by

favourite enjoyment. The fire on board and the valiant efforts by the Master to

put off the fire risking his life were all revealed from the documents. That

the fire was not due to the actual fault or privity of the carrier and that the

carrier was entitled to rely on the exception in the bill of lading was very

evident.

The

decision of the House Lords in MV Indian

Grace had deeply affected the features of the in rem action till then exercised by English Courts. It was so

important a land mark that, authors identified the different phases of legal

growth by terming them as period before MV

Indian Grace and after MV Indian

Grace. Higher courts across the Common law world took note and relied on

the decision in MV Indian Grace.

Acknowledged experts on Maritime Law like A.M. Sheppard opined in their

treatises that the decision was capable of drastically affecting some features

of the action in rem followed in

England till then. Since the House of Lords had relied on the Judgment of the

Subordinate Judges Court Cochin in striking off the English action, the

correctness of the said Judgment of the Sub court to be considered by the

Kerala High Court in the appeal assumed relevance.

To

my excitement the appeal was finally posted for consideration before a division

Bench of the High Court of Kerala. After a fair share of adjournments from the

part of the Government, the matter was taken up for final hearing and disposal.

The senior presiding Judge being a former Civil Lawyer of standing and repute

picked up the relevant facts deftly. The appeal was heard for days together.

After noons were specifically set apart for exclusive hearing of the appeal.

Carriers liability and intricacies of the term “actual fault and privity of the carrier” were considered by the

Judges in detail. Scores of reports on the point from Lloyds Law Reports were

placed before the bench by both sides. The response from the Bench was

encouraging. It appeared that the Bench was convinced about the protections

that the carrier and the vessel are entitled to under law. An important

Judgment as a sequel to that of the House of Lords was in the immediate offing.

But

before the Judgment could be rendered, to my dismay, the appeal was transferred

to another Division Bench. We were back to square one. The presiding Judge here

was a seasoned lawyer well aware of commercial legal practise. The Bench echoed

the views of the earlier bench. Hearing went on for days. It would start off

with a quip by the Judge, “Lets sail with

Indian Grace.” Both sides argued in detail. Senior lawyer in the rank of

Assistant Solicitor General of India appeared and argued for the Government.

The Judge gave a peek of his mind by opining that the precedents and facts

called for interference with the judgment of the sub-court. After days of

lengthy hearing the new Division Bench proceeded to reserve the matter of

dictation. We eagerly awaited a judgment capable of reporting across the

maritime world from Kerala High Court, one that would be taken note of by

English Lawyers and maritime experts.

But

MV Indian Grace was not destined to

have a smooth legal journey. Before the date on which the judgment was to be

delivered, the case was posted before the Bench by a process called ‘to be

spoken to’. It was submitted on behalf of the Government of India that an

amendment is proposed to be moved to hike the claim amount which at present was

only for the short landed cargo. The Attorney General of India had in view of

the failure of the English action, apparently suggested claiming a constructive

total loss of the entire cargo and thus to enhance the claim amount from few

lakhs to crores of Rupees. The rendering of judgment was thus sought to be

adjourned to facilitate the filing of the amendment petition and the same was

allowed. I had no reason to feel alarmed as the earlier two division Benches

had been convinced of the case and was eager to render a detailed judgment

touching upon all aspects of the case.

Within

a week the appeal came up before another division bench. The suggested amendment had not yet been

carried and instead of seeking time for pursuing the same, the Government

pressed for urgent hearing before the new bench. The hearing of MV Indian Grace thus commenced before the third division bench. Suffice to say that the

Bench wound up the hearing within twenty five minutes and proceeded to deliver

judgment dismissing the appeal.

Winning

the appeal though was a prime objective was not the sole objective. All through the hearing the single minded and

earnest desire was that the judgment from the High Court of Kerala based on the

detailed arguments placed by both sides touching on importance question of

maritime law and carriage of goods by sea would lead to a judgment that will be

a befitting sequel to the decision of the House of Lords in MV Indian Grace. The judgment that was finally rendered ran to

less than four pages and carried a sentence to the effect that though numerous

foreign decisions were placed before the Bench the same are not felt relevant

to be discussed. Thus ended the long journey of MV Indian Grace.

I

returned to office carrying the bundle which had now become huge with numerous

copies of decisions from Lloyds reports.

I was visited by my senior partner with a comforting smile. He shared

with me the wisest advice which I treasure all through the rest of my career.

First one was “Never identify personally

with the subject matter of your case however interesting it may be.” This

was followed by a very practical advise which went like this. “When a case that had been heard at length by

a Bench and is expected to be decided in your favour is sought to be adjourned

by the opposite side, pray to the court that the same may be noted on file as PART

HEARD.” This would have ensured that the matter would again come up only

before the same Bench!

I

realised that my theoretical knowledge of maritime law and my rummaging through

volumes of Lloyds Law reports are no substitute to practical lawyering skills

which can be acquired only through years of patient dedicated practise.

Let me leave you with a sequel to this story.

Around ten years after the above experience, at a private function I ran into

the same Judge who had heard the MV

Indian Grace appeal on its second round. He had since retired and to my

surprise very well remembered the quip of sailing with Indian Grace. He told me that he had already dictated a detailed

Judgment allowing the appeal filed by MV

Indian Grace and same was not

typed out and issued since the matter got adjourned.

***