ARREST OF SHIPS FOR ENFORCING MARITIME CLAIMS

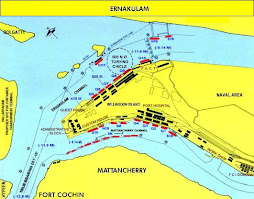

Arrest of merchant vessels calling at Cochin by the High Court of Kerala has increased in recent times. Though the same ought to be a matter of concern for the entire shipping community at Cochin, it has not received the attention it deserves.

The spurt in the number of arrests has revealed the vulnerability of the vessels calling at the Cochin port. At a time when the shipping prospects of Cochin are brightening and vessels including mother ships and large cruise liners are calling at Cochin almost on a daily basis, it is in the interest of the shipping community, especially the Liners and their agents acting from Cochin, that the law pertaining to the arrest of sea going vessels is stream lined and updated to meet the needs of the time.

Arrest and detention of a foreign vessel towards enforcing a maritime claim is a potent weapon in the hands of a person which ensures that his lawful claim is protected when the claim is ultimately decided in his favor by a Court of law. But in the hands unscrupulous persons the same can be used as a means to pressurize the vessel and its owners to heed to the illegal and unjustified demands raised by the claimant. The right of a person to seek arrest of a vessel has to be clearly circumscribed and demarcated so as to ensure that the said right is never misused. Unfortunately the law relating ship arrests as it now exists, is devoid of safe guards to prevent an unscrupulous or malicious arrest.

The lack of clarity in law regarding arrest has even lead to situations where the Court arrests vessels lying in Ports as far off as Mumbai in purported claims that have nothing to do with Cochin or Kerala and even where the concerned vessel has never even called at Cochin Port. Cochin has thus become a convenient forum for raising frivolous maritime claims seeking arrest of vessels and for compelling ship owners to satisfy the illegal demands which in the long run does not augur well for the shipping community here.

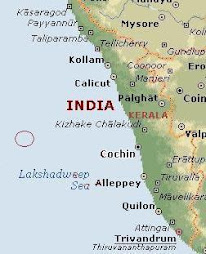

All this is because there exists no comprehensive code for shipping laws laying down the legal norms both substantive and procedural, governing different aspects of admiralty. The law that presently governs the power to arrest sea going vessels in India can be traced to the Colonial Courts of Admiralty Act, 1891 which conferred Admiralty Jurisdiction including the power to arrest and detain a vessel, on the Chartered High Courts of erstwhile British India. After independence like in many other walks of life admiralty law too failed to keep pace with the changing times. This legislative lacunae was sought to be plugged to a certain extent by Justice Kochu Thommen, Supreme Court of India in the celebrated decision of mv Elizabeth by holding inter alia that all High Courts in India being superior courts of record possess inherent admiralty jurisdiction. By virtue of the said decision, the High Court of Kerala too possess admiralty jurisdiction over vessels situated within its territorial limits. Thus any vessel within the territorial waters of Kerala and Lakshadweep falls within the admiralty jurisdiction of the High Court of Kerala and can be arrested or detained pursuant to a maritime claim.

The substantive law thus having been taken care of by the Supreme Court, now the procedural vacuum comes to the fore. Chartered High Courts like Mumbai, Calcutta and Chennai possess original civil jurisdiction and maritime claims along with petitions seeking arrest of the vessel are filed before the said High Courts as Civil Suits by remitting the mandatory court fee which would depend on the suit amount. The same acts as a check on frivolous litigations since by and large only genuine claimants would choose to deposit court fee and initiate a proceeding against a vessel and seek its arrest. Any frivolous arrest would be visited with exemplary damages. These High Courts have also evolved detailed Admiralty Rules to deal with the procedural aspects of cases involving vessels.

The situation as it exists in Kerala is different in so far as the High court of Kerala does not exercise original civil jurisdiction in admiralty matters. Though in the light of the decision in mv Elizabeth High Courts in certain other states similarly placed as the High Court of Kerala have got over the said hurdle by evolving Rules governing admiralty practice, no such rule has been evolved by the Kerala High Court. Hence an action seeking arrest of a vessel is filed before the High Court of Kerala as a Writ Petition under Article 226 of the Constitution seeking a direction to the Port authorities to detain the vessel relying on Sec. 443 of the Merchant Shipping Act, 1956. The inherent defect of the said exercise which relegates Cochin as a favorite destination through forum shopping is that an arrest motion can be filed here with out depositing a farthing inspite of the fact that the claim raised against the impugned vessel would run to any fanciful amount at times to crores of Rupees. As the Court is not equipped to delve into questions of fact while exercising its jurisdiction under Article 226, the complicated factual matters that are invariably involved in all maritime claims cannot be looked in to by the High Court. Thus all that the Court does is to issue an arrest mostly ex parte and direct that the vessel be detained unless the claim amount in full is not deposited or an equivalent bank guarantee is provided for the said amount. Apprehensive of disrupting schedules, the vessel chooses to provide the bank guarantee than risk a prolonged arrest and detention. Once the Bank Guarantee is furnished, the matter is relegated to the appropriate civil court where a long drawn civil battle awaits the vessel and its owners for the entire period of which the Bank guarantee has to be kept alive. Banks insist on heavy interest for keeping the bank guarantee live for inordinate long period and this acts as an economic duress on the vessel owner to settle the matter at the earliest at terms favourable to the claimant.

The civil law right to file a general caveat which is available to the ship owner to preempt the arrest motion and to be informed of the same before an actual arrest order is issued, which is available to him before the High Courts like Mumbai is not available to him in Cochin, based on the reasoning that no caveat would lie in a writ proceeding. Though the right to file a caveat as envisaged in the Civil Procedure Code does exist and can be availed, many a time, the vessel or its owners would not be in a position to know before hand the name, address and other details of the person or entity that might move for an arrest. It is to take care of such eventualities that in High Courts like Mumbai, filing of a general caveat is permitted which is filed by the vessel or its owners against the world at large and before any motion for arrest is issued, notice would be given to the vessel or to its representative. Thus surprise arrests which are a bane in Cochin and damaging to its interest could be avoided.

Early initiatives are to be taken by the shipping community of Cochin towards altering the above scenario and towards evolving legal norms that would plug the present loopholes of law. If the proposed development activities in the Cochin Port and the infrastructural additions in the anvil are to achieve its desired ends, appropriate changes have to be made to the legal norms governing admiralty matters too.

Law may be only one among the many platforms from which the eternal battle for social and economic progress of the community has to be fought. But we ought not forget that it is too important a platform to be ignored in the developmental process.

* * *

POST SCRIPT: New directions in Admiralty Jurisdiction in Kerala – Recent change in law pursuant to the judgment in MV FREE NEPTUNE case.

When a Judge proceeds to fill in a legal lacuna, there are some inherent limitations which he may have to confront. He may be able to legislate to a limited extent within the interstices but not beyond. If he attempts to proceed past the threshold, he may flounder. Nevertheless, the eagerness to render justice may entice him to walk that extra mile.

The case of MV FREE NEPTUNE v. D.L.F. SOUTHERN TOWNS PVT. LTD. [2011 (1) KLT 904] is a typical example of a Judgment where a Court earnestly grapples with a pressing issue, intending to set the law straight but finds itself seriously limited and tied down on to many counts. The said Judgment of the Hon’ble High Court of Kerala has altered the procedure regarding invocation and exercise of admiralty jurisdiction of the High Court. A new procedure has been laid down by the Hon’ble Division Bench which is to hereinafter govern the invocation of admiralty jurisdiction in the High Court of Kerala until specific Admiralty Rules are framed by the High Court.

The Judgment requires close study since it contains certain areas of genuine concern for the maritime circles especially in the port city of Cochin which has the only International Transshipment Terminal in India.

The case involved a vessel by the name MV FREE NEPTUNE. While she was berthed in the Port of Chennai, State of Tamil Nadu the High Court of Kerala in a motion alleging short landing of cargo at Cochin arrested her. The vessel thus situated beyond the territorial limits of the High Court of Kerala was arrested by a single judge of the Hon’ble High Court vide an interim Order. The said Interim Order also provided for release of the vessel upon furnishing stipulated security, which was duly furnished by the vessel and release was obtained. Subsequent thereto, the alleged short landed cargo which had been discharged in Chennai was transported to Cochin and the vessel moved for return of the security already furnished. The Learned Single judge refused to order return of security. An amendment motion and a prayer for impleading additional parties were duly allowed by the Learned Single Judge. Appeals were preferred before the Hon’ble Division Bench against the orders of the Learned Single Judge by concerned interests. The Division Bench seized the opportunity which thus presented to itself before it and proceeded to structure the exercise of admiralty jurisdiction in Kerala as could be discerned from the following observation in the Division Bench Judgment:

“It may be stated here that there is no statute or any other instrument known to law structuring the admiralty jurisdiction of the High Court of Kerala. No rules are framed by this Court regarding the regulation of the admiralty proceedings before this Court. It is in the said back ground, we thought it fit to withdraw the Sp.J.C. also for a comprehensive examination of these various issues for the purpose of not adjudicating the questions involved in the Sp.J.C., but for the purpose of settling the ambit of the admiralty jurisdiction of this Court and the procedure to be followed in exercising such jurisdiction.”

The Hon’ble Court thus proceeded to settle the ambit of the admiralty jurisdiction of the High Court of Kerala and also to lay down the procedure to be followed for exercising admiralty jurisdiction.

As pointed out in the first part of this article, there was of course a pressing need for structuring and refining the admiralty jurisdiction as exercised by the High Court of Kerala. That the Division Bench attempted to do so was salutary. The Judges had intended to iron out the crevices and brightening the grey areas surrounding the exercise of admiralty jurisdiction in Cochin. Thus even though the Judgment started of well with a salutary objective, what finally resulted was something akin to the proverbial throwing of the baby out along with the bath water. Suffice to say that subsequent to the said Judgment, moving the High Court of Kerala to obtain an arrest of a foreign vessel has become onerous for genuine litigants.

It is doubtful whether the choice of Free Neptune as the case to lay down the law relating to admiralty jurisdiction of the High Court of Kerala was correct in the first place. The motion for seeking to arrest the vessel Free Neptune, which during the relevant time was lying in the Port of Chennai in the State of Tamil Nadu beyond the territorial jurisdiction of the High Court of Kerala was fit to be dismissed at the threshold by simply following the precedent laid down by the Hon’ble High Court of Kerala itself in the Judgment of Ocean Lanka Shipping Co (Pvt.) Ltd. v MV Janate [1997(1) KLT 369]. The said Judgment had already laid down the law regarding the jurisdictional limit for exercise of admiralty jurisdiction of the High Court of Kerala. In the said case, the Hon’ble Court had refused to arrest a vessel lying in Mangalore in the state of Karnataka stating that the vessel is not anchored within the jurisdiction of the High Court of Kerala. Thus it is doubtful whether the Hon’ble High Court of Kerala, the jurisdictional limits of which are specifically confined to the state of Kerala and the Union Territory of Lakshadweep had territorial jurisdiction to arrest Free Neptune lying in Chennai Port. The vessel was clearly within the admiralty jurisdictional limits of the High Court of Madras which is a chartered High Court and had all power to invoke its jurisdiction over it. The question of territorial jurisdiction which ought to be the starting point of any adjudication was not dwelt upon and the precedent laid down by Ocean Lanka Shipping Co. was not referred to. Judgments of the High Court of Bombay in Kamala Kant Dube v. M.V. Umang and the High Court of Madras in M/s Seawaves Shipping Services v. M/s Adriatic Tankers and Mayar HK Ltd. v. M.V. Neetu ought to have been considered in the said respect. It has been held by a Division Bench in Reena Padhi v. Owners of Motor Vessel Jagdhir [AIR 1982 Orissa 57] as follows: “It cannot be said that all High Courts in India exercising admiralty jurisdiction have concurrent powers to entertain causes of action….” In Shipping Fund Development Committee v. M.V. Charisma [AIR 1981 BOMBAY 42] the learned judge stated as follows: “It would seem that consequent upon the enactment of the 1958 Act, the admiralty Court has lost its country wide jurisdiction to entertain suits to enforce ship mortgages and retains it only within the limits of particular courts appellate jurisdiction….” Had those aspects been taken note of, it is doubtful whether the Learned Judges would have chosen the case of Free Neptune as the fit case to structure and lay down the law regarding admiralty jurisdiction in Kerala.

How does the Free Neptune Judgment affect different sections of the maritime community in Cochin? The judgment cuts both ways. But it hits the cargo interests harder. Cargo interests from Cochin like sea food exporters who suffer loss due to negligent carriage will find it cumbersome to initiate legal action in Cochin, their home town, for recovery against the erring foreign vessel. They now have to deposit court fee commensurate to their plaint claim, which of course cannot be termed as unfair, but commercial prudence will compel them to travel to Mumbai and initiate a litigation in the High Court of Bombay, though it is an unknown turf infamous for back log of cases, merely because the court fee payable there would be substantially less than what they may have to pay in Kerala. Even when offending vessel is found berthed right in Cochin, the litigants would thus rush to Bombay for moving the Admiralty Court finally to no avail since there is every chance that by the time an arrest order is obtained from Bombay High Court, the vessel sailed out to her next port of call out of India. The judgment in its effect would not spare the Ship or its owners/charterers either. Though the Judgment has the obvious beneficial side that frivolous arrest of vessels at the drop of a hat would be averted, since the arrest when it actually comes would come from Mumbai and other Chartered High Courts outside Kerala possibly from Calcutta too, for obtaining release of the vessels they may have to move the very same Courts.

The felt necessity of the trade was only to prevent frivolous arrests by plugging the lacunae in law regarding exercise of admiralty jurisdiction by the High Court of Kerala. All that was needed was some norms which would prevent the misuse and wrongful invocation of admiralty jurisdiction. It could have been achieved by a much simpler process than by rocking the proverbial boat and ultimately leading to its capsizing.

A motion for arrest of a foreign vessel is made for the limited purpose of ensuring that the vessel does not slip out of the territorial jurisdiction without providing sufficient security before the dispute is adjudicated and final decision is arrived at. At the time when the arrest motion is made, the claim would be in a nascent stage. It is not necessary that the vessel should continue to remain within the territorial jurisdiction while the claim is adjudicated on its merits. The vessel could sail off after providing a security so that the dispute can be adjudicated at leisure. The security thus furnished would be kept alive till the final culmination of the claim in a Judgment/Decree or an Award. The claim may have been either allowed or dismissed. If the same is allowed, fully or partially, the same could be realized from the security provided. This being the limited objective of filing an arrest motion invoking admiralty jurisdiction, couldn’t this have been easily achieved by the structuring exists norms?

High Court of Kerala does not have Original Civil Jurisdiction. But the Hon’ble Division Bench has in Free Neptune Judgment laid down the law to be followed in the future as follows:

“This Court did not so far frame any Rules regulating the procedure for adjudicating the disputes arising under the admiralty jurisdiction. Therefore we deem is appropriate to declare that henceforth any person approaching this court invoking the admiralty jurisdiction shall institute a suit in accordance with the procedure contemplated under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908. Such suits shall be tried by this Court following the procedure prescribed under the Code of Civil Procedure.”

In view of the above law now laid down by the Hon’ble Court, any one who herein after chooses to invoke the admiralty jurisdiction of the High Court of Kerala, will have to do so by instituting a civil suit. Some interesting situations could arise. Since according to the dictum filing of civil suits are necessary only in case of invocation of “admiralty jurisdiction of the High Court of Kerala”, in Socratic sense we may have to define our terms at the threshold. What exactly is the scope and ambit of the term “admiralty jurisdiction”? We are readily assisted by the definition as laid down in Section 20 of the Supreme Court Act, 1981 (which is a statute of United Kingdom and has engaged the attention of the Learned Judge’s as revealed from para 19 of the Free Neptune Judgment). Sec.20 of the said Act states that Admiralty Jurisdiction of the High Court shall include the Jurisdiction to hear and determine any questions and claims mentioned in sub clause (2) of the Act. The said sub-clause (2) enumerates under (a) to (s) the questions and claims. Sub-clause 2 (e), (g) and (h) are of direct interest. (e) speaks of any claim for damage done by a ship, (g) any claim for loss or damage to goods carried in a ship, and (h) any claim arising out of any agreement relating to the carriage of goods in a ship or to the use or hire of a ship. [Sub clause (f) also would assume relevance depending on whether the term “Personal Injury” used therein is wide enough to take in an injury/loss suffered by a cargo owner due to damage or short landing of cargo. Let’s save if for another time].

This definition of Admiralty Jurisdiction of the High Court as laid down in Section 20 of the Supreme Court Act, 1981 is in pari materia with the definition of “Maritime claim” in the 1952 Brussels Convention on Arrest of Ships.

What follows is that since the Learned Judges have in Free Neptune laid down a law that hereinafter all motions invoking the ‘admiralty jurisdiction’ of the High Court of Kerala shall be civil suits, and since the term ‘admiralty jurisdiction’ as examined above herein above takes in ‘any claim for damage done by a ship’, ‘any claim for loss or damage to goods carried in a ship’, and ‘any claim arising out of any agreement relating to the carriage of goods in a ship or to the use or hire of a ship’, it may be open to file suits for realizing said claims before the Hon’ble High Court of Kerala invoking its admiralty jurisdiction. Strangely enough, small civil suits for such paltry sums as Rs.50,000/- which hitherto were filed in the Subordinate Judges Court, Cochin could possibly be filed before the Hon’ble High Court of Kerala invoking its admiralty jurisdiction. Whether it’s desirable that the Highest Court of the land, which since its inception has not handled civil suits and is insufficiently equipped (administratively) for handling prolonged civil trials involving complex maritime legal issues, should now commence adjudicating such cases is a question to be pondered on.

Moreover, is it necessary for the Hon’ble High Court to relegate to itself all suits involving maritime claims? Even more so since all suits pertaining to maritime claims need not necessarily contain a relief for arresting a foreign vessel and could simply be a suit for money arising out of a carriage of goods by sea contract. Thus all maritime claims need not lead to invocation of admiralty jurisdiction in the sense of arresting the defaulting ship. Such maritime claims which are pure and simple civil suits could as well be adjudicated by the Subordinate Judge’s Court as is presently being done, the said courts being well equipped to deal with such complex questions requiring appreciation of evidence in detail.

Another equally interesting situation looms large due to the said laying down of law in Free Neptune. It relates to Sec. 443 of the Merchant Shipping Act, 1958. The said provision too has engaged the attention of the learned Judges while rendering Free Neptune Judgment as can be revealed from para 20. Sec. 443 speaks about detention of a foreign vessel while within Indian Jurisdiction. The difference between ‘Arrest’ and ‘Detention’ of a ship assumes significance here. Arrest practically and theoretically is graver than Detention. Detention is a condition which the ship endures more than frequently during her life. It is less rigorous from Arrest, both in cause and effect. A detailed exposition of the difference may be out of place here, suffice to say in the context of Sec.443 that the term Arrest has been purposefully excluded by the Legislature in Secs. 443 and 444 of the Act. Instead it only speaks of detention. A co-joint reading of the said two sections will reveal that power of detention exists both in the High Court as well as on an officer of the port (albeit temporarily). Thus detention is a power evidently different from Arrest which as is said to exist only in the Highest Courts of Record having plenary power. An officer of the port may not be able to arrest a ship though he could detain it on various grounds one of which could be as explained in Sec.443 (2). The Hon’ble Supreme Court also while discussing powers under 443 and 444 termed them as merely procedural and substantive rights like that of Arrest lies else where. Coming back again to Free Neptune judgment lets examine how the dictum therein that civil suits alone could be filed invoking admiralty action, impact Secs. 443 and 444 of Merchant Shipping Act, 1958? A motion under Sec.443 to the High Court will have all the draping of and resemblances to a ‘maritime claim’ and to an ‘admiralty action’. It will for sure involve a foreign ship which might have caused damage to or loss to the cargo of an Indian citizen and the claim could lead to a claim over the vessel herself. Sec. 443 does not state that a civil suit has to be preferred for invoking the procedure laid down therein. If he moves the High Court purporting to invoke 443 he ought not be compelled to file a civil suit stating that his motion has all draping of invocation of admiralty jurisdiction. By all means the procedure laid down under Sec.443 for moving the High Court was a special jurisdiction conferred on the High Court. It was made part of the statute in 1958, at a time when admiralty jurisdiction and arrest was being exercised by the chartered High Courts in India. It was thus a procedural right available to an Indian Citizen against a foreign ship in addition to the right of arrest which he may have had under general law. The nomenclature Special Jurisdiction Case (Sp.J.C.) hitherto followed by the Registry of the High Court of Kerala while numbering motions made under Sec. 443 was thus apt and correct. The right vested in an Indian Citizen under Sec.443 of the Act to seek detention (not arrest) by moving the High Court will be effectively curtailed if his remedy to seek enforcement thereof could be invoked only by way of filing a civil suit as now seen laid down in Free Neptune. The situation will be even direr if the officer contemplated under Sec. 443 (2) refuses to exercise his power to detain the vessel notwithstanding existence of all prerequisites for such detention and a motion seeking mandamus is resisted contending that only suit is maintainable in the facts of the case. In effect, does the Judgment in Free Neptune exclude from its ambit motions under Sec.443? Can a writ or a Sp.J.C still lie to the High Court under Sec.443? The problems arising from the interplay of the provisions of the Merchant Shipping Act conferring jurisdiction on the High Court and the inherent powers of the High Court can be well gauged from the decision in Shipping Fund Development Committee v. M.V. Charisma [AIR 1981 BOMBAY 42].

In Free Neptune, after thus laying down the procedure to be followed for invoking the admiralty jurisdiction, the Hon’ble Court proceeded to lay down the law applicable till proper Rules are framed by the High Court. “We also declare that Rules framed by the Madras High Court in so far as they are not inconsistent with any other provision of law for the time being in force and with appropriate modifications shall apply to the conduct of such suits until this Court modifies the said Rules or the legislature intervenes in this regard.”

The choice of the Madras Rules as applicable during the interregnum was explained by the Hon’ble Court as follows: “ We make such a declaration not only because we owe an obligation under law to devise a procedure for the regulations of the proceedings before this Court as was pointed out by the Supreme Court in Elisabeth’s case at para 64… but also for the reason that a part of the territory over which this High Court now exercise jurisdiction was within the territorial jurisdiction of the Madras High Court prior to the States Reorganization Act, 1956. Therefore, for at least that part of the territory of the State of Kerala, which was within the jurisdiction of the Madras High Court prior to the States Reorganization Act, 1956 was governed by the law administered by the Madras High Court which devolved upon this Court by virtue of the operation of Section 52 of the States Reorganization Act, 1956.”

Since the Hon’ble Court was involved in the very crucial exercise of devising a procedure for the regulations of the proceedings before itself, a closer scrutiny would have been desirable. Cue could have been taken from the detailed exposition regarding similar question of admiralty jurisdiction of Orissa High Court in Reena Padhi v. Owners of Motor Vessel Jagdhir [AIR 1982 Orissa 57].

Moreover the reliance placed on and interpretation given to Sec. 52 of the States Reorganization Act, 1956 to justify the adoption of Madras Rules is not free from doubt. Erstwhile Malabar district which was an administrative district of former Madras Presidency is now part of Kerala state. But all along the west coast of India including over the erstwhile Malabar district, High Court of Bombay as a colonial court of admiralty had exercised admiralty jurisdiction especially since the old chartered high courts has been exercising overlapping admiralty jurisdiction. Even offlate the High Court of Bombay has been arresting ships berthed in Chennai. Since the law as applicable along the west coast including Malabar and the entire coast of Kerala, was the admiralty law as enforced by the High Court of Bombay, the more appropriate course of action to be adopted during the interregnum would have been to apply the Admiralty Rules of Bombay as it was ‘the law in force’ over that part of the state of Kerala ‘immediately before the appointed day’ as envisaged Sec. 52 of the States Reorganization Act, 1956.

Arrest of a vessel invoking admiralty jurisdiction is an action in rem. It is an action against a res or a thing and against unascertained persons, i.e., against the world at large, thus binding any one who has a real and subsisting interest in the res. All that is necessary is to retain the power of the High Court to entertain an action in rem thus retaining the power of the High Court to entertain an arrest motion under admiralty jurisdiction and to structure and refine its exercise. It is desirable that the inherent admiralty jurisdiction of the High Court in a motion in rem is confined to arrest of the relevant vessel found within its jurisdiction and upon furnishing of security by the person interested in the vessel, the action in rem thus being converted to an action in personam, the parties ought to be relegated back to the appropriate forum to fight out their action in personam by way of a suit or arbitration during the pendancy of which the security furnished should be kept alive. The system in place in High Court of Kerala before the Free Neptune judgment had effectively ensured the above. The principal draw back was that there was no sufficient safeguard against frivolous invocation of admiralty jurisdiction and consequent arrest of ships. The situation has to be remedied first by ensuring that no arrests orders are made by the High Court of vessels berthed beyond its territorial limits.

The need for retaining a special jurisdiction as Admiralty Jurisdiction is itself debatable. However, accepting the peculiar nature of maritime transactions and assuming that there is a need for treating them separately (see Sec. 112 of the CPC), are there any compelling reasons for the highest court of the state, already over burdened with litigations, to proceed to consider civil suits involving complex commercial questions of maritime law and facts which would require elaborate appreciation of evidence.

The judgment in Free Neptune case points out to the urgent need for a comprehensive legislation regarding admiralty law in India. It can be reasonably discerned from the slow death of the Admiralty Bill, 2005 that such a wait could be a fairly long one. Till then the only solution to the impasse appears to be adoption of comprehensive Admiralty Rules by the High Court of Kerala. The Admiralty Rules in force in Madras, Bombay or Calcutta have all become thoroughly outdated and needs fine tuning to meet the felt necessities of time and trade. A verbatim adoption or transplanting of any of such Rules as the Rules for the High Court of Kerala would only complicate things further since the very character of the said courts and the Kerala High Court are different. Being the only International Transshipment Terminal in India undertaking maritime activity of a unique nature, let’s hope that the Admiralty Rules to be evolved by the High Court would take note of the felt necessities of international trade as pointed out by the Supreme Court in MV Elizabeth case and noted with approval by the Hon’ble High Court of Kerala in the case of Free Neptune.

When a Judge proceeds to fill in a legal lacuna, there are some inherent limitations which he may have to confront. He may be able to legislate to a limited extent within the interstices but not beyond. If he attempts to proceed past the threshold, he may flounder. Nevertheless, the eagerness to render justice may entice him to walk that extra mile.

The case of MV FREE NEPTUNE v. D.L.F. SOUTHERN TOWNS PVT. LTD. [2011 (1) KLT 904] is a typical example of a Judgment where a Court earnestly grapples with a pressing issue, intending to set the law straight but finds itself seriously limited and tied down on to many counts. The said Judgment of the Hon’ble High Court of Kerala has altered the procedure regarding invocation and exercise of admiralty jurisdiction of the High Court. A new procedure has been laid down by the Hon’ble Division Bench which is to hereinafter govern the invocation of admiralty jurisdiction in the High Court of Kerala until specific Admiralty Rules are framed by the High Court.

The Judgment requires close study since it contains certain areas of genuine concern for the maritime circles especially in the port city of Cochin which has the only International Transshipment Terminal in India.

The case involved a vessel by the name MV FREE NEPTUNE. While she was berthed in the Port of Chennai, State of Tamil Nadu the High Court of Kerala in a motion alleging short landing of cargo at Cochin arrested her. The vessel thus situated beyond the territorial limits of the High Court of Kerala was arrested by a single judge of the Hon’ble High Court vide an interim Order. The said Interim Order also provided for release of the vessel upon furnishing stipulated security, which was duly furnished by the vessel and release was obtained. Subsequent thereto, the alleged short landed cargo which had been discharged in Chennai was transported to Cochin and the vessel moved for return of the security already furnished. The Learned Single judge refused to order return of security. An amendment motion and a prayer for impleading additional parties were duly allowed by the Learned Single Judge. Appeals were preferred before the Hon’ble Division Bench against the orders of the Learned Single Judge by concerned interests. The Division Bench seized the opportunity which thus presented to itself before it and proceeded to structure the exercise of admiralty jurisdiction in Kerala as could be discerned from the following observation in the Division Bench Judgment:

“It may be stated here that there is no statute or any other instrument known to law structuring the admiralty jurisdiction of the High Court of Kerala. No rules are framed by this Court regarding the regulation of the admiralty proceedings before this Court. It is in the said back ground, we thought it fit to withdraw the Sp.J.C. also for a comprehensive examination of these various issues for the purpose of not adjudicating the questions involved in the Sp.J.C., but for the purpose of settling the ambit of the admiralty jurisdiction of this Court and the procedure to be followed in exercising such jurisdiction.”

The Hon’ble Court thus proceeded to settle the ambit of the admiralty jurisdiction of the High Court of Kerala and also to lay down the procedure to be followed for exercising admiralty jurisdiction.

As pointed out in the first part of this article, there was of course a pressing need for structuring and refining the admiralty jurisdiction as exercised by the High Court of Kerala. That the Division Bench attempted to do so was salutary. The Judges had intended to iron out the crevices and brightening the grey areas surrounding the exercise of admiralty jurisdiction in Cochin. Thus even though the Judgment started of well with a salutary objective, what finally resulted was something akin to the proverbial throwing of the baby out along with the bath water. Suffice to say that subsequent to the said Judgment, moving the High Court of Kerala to obtain an arrest of a foreign vessel has become onerous for genuine litigants.

It is doubtful whether the choice of Free Neptune as the case to lay down the law relating to admiralty jurisdiction of the High Court of Kerala was correct in the first place. The motion for seeking to arrest the vessel Free Neptune, which during the relevant time was lying in the Port of Chennai in the State of Tamil Nadu beyond the territorial jurisdiction of the High Court of Kerala was fit to be dismissed at the threshold by simply following the precedent laid down by the Hon’ble High Court of Kerala itself in the Judgment of Ocean Lanka Shipping Co (Pvt.) Ltd. v MV Janate [1997(1) KLT 369]. The said Judgment had already laid down the law regarding the jurisdictional limit for exercise of admiralty jurisdiction of the High Court of Kerala. In the said case, the Hon’ble Court had refused to arrest a vessel lying in Mangalore in the state of Karnataka stating that the vessel is not anchored within the jurisdiction of the High Court of Kerala. Thus it is doubtful whether the Hon’ble High Court of Kerala, the jurisdictional limits of which are specifically confined to the state of Kerala and the Union Territory of Lakshadweep had territorial jurisdiction to arrest Free Neptune lying in Chennai Port. The vessel was clearly within the admiralty jurisdictional limits of the High Court of Madras which is a chartered High Court and had all power to invoke its jurisdiction over it. The question of territorial jurisdiction which ought to be the starting point of any adjudication was not dwelt upon and the precedent laid down by Ocean Lanka Shipping Co. was not referred to. Judgments of the High Court of Bombay in Kamala Kant Dube v. M.V. Umang and the High Court of Madras in M/s Seawaves Shipping Services v. M/s Adriatic Tankers and Mayar HK Ltd. v. M.V. Neetu ought to have been considered in the said respect. It has been held by a Division Bench in Reena Padhi v. Owners of Motor Vessel Jagdhir [AIR 1982 Orissa 57] as follows: “It cannot be said that all High Courts in India exercising admiralty jurisdiction have concurrent powers to entertain causes of action….” In Shipping Fund Development Committee v. M.V. Charisma [AIR 1981 BOMBAY 42] the learned judge stated as follows: “It would seem that consequent upon the enactment of the 1958 Act, the admiralty Court has lost its country wide jurisdiction to entertain suits to enforce ship mortgages and retains it only within the limits of particular courts appellate jurisdiction….” Had those aspects been taken note of, it is doubtful whether the Learned Judges would have chosen the case of Free Neptune as the fit case to structure and lay down the law regarding admiralty jurisdiction in Kerala.

How does the Free Neptune Judgment affect different sections of the maritime community in Cochin? The judgment cuts both ways. But it hits the cargo interests harder. Cargo interests from Cochin like sea food exporters who suffer loss due to negligent carriage will find it cumbersome to initiate legal action in Cochin, their home town, for recovery against the erring foreign vessel. They now have to deposit court fee commensurate to their plaint claim, which of course cannot be termed as unfair, but commercial prudence will compel them to travel to Mumbai and initiate a litigation in the High Court of Bombay, though it is an unknown turf infamous for back log of cases, merely because the court fee payable there would be substantially less than what they may have to pay in Kerala. Even when offending vessel is found berthed right in Cochin, the litigants would thus rush to Bombay for moving the Admiralty Court finally to no avail since there is every chance that by the time an arrest order is obtained from Bombay High Court, the vessel sailed out to her next port of call out of India. The judgment in its effect would not spare the Ship or its owners/charterers either. Though the Judgment has the obvious beneficial side that frivolous arrest of vessels at the drop of a hat would be averted, since the arrest when it actually comes would come from Mumbai and other Chartered High Courts outside Kerala possibly from Calcutta too, for obtaining release of the vessels they may have to move the very same Courts.

The felt necessity of the trade was only to prevent frivolous arrests by plugging the lacunae in law regarding exercise of admiralty jurisdiction by the High Court of Kerala. All that was needed was some norms which would prevent the misuse and wrongful invocation of admiralty jurisdiction. It could have been achieved by a much simpler process than by rocking the proverbial boat and ultimately leading to its capsizing.

A motion for arrest of a foreign vessel is made for the limited purpose of ensuring that the vessel does not slip out of the territorial jurisdiction without providing sufficient security before the dispute is adjudicated and final decision is arrived at. At the time when the arrest motion is made, the claim would be in a nascent stage. It is not necessary that the vessel should continue to remain within the territorial jurisdiction while the claim is adjudicated on its merits. The vessel could sail off after providing a security so that the dispute can be adjudicated at leisure. The security thus furnished would be kept alive till the final culmination of the claim in a Judgment/Decree or an Award. The claim may have been either allowed or dismissed. If the same is allowed, fully or partially, the same could be realized from the security provided. This being the limited objective of filing an arrest motion invoking admiralty jurisdiction, couldn’t this have been easily achieved by the structuring exists norms?

High Court of Kerala does not have Original Civil Jurisdiction. But the Hon’ble Division Bench has in Free Neptune Judgment laid down the law to be followed in the future as follows:

“This Court did not so far frame any Rules regulating the procedure for adjudicating the disputes arising under the admiralty jurisdiction. Therefore we deem is appropriate to declare that henceforth any person approaching this court invoking the admiralty jurisdiction shall institute a suit in accordance with the procedure contemplated under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908. Such suits shall be tried by this Court following the procedure prescribed under the Code of Civil Procedure.”

In view of the above law now laid down by the Hon’ble Court, any one who herein after chooses to invoke the admiralty jurisdiction of the High Court of Kerala, will have to do so by instituting a civil suit. Some interesting situations could arise. Since according to the dictum filing of civil suits are necessary only in case of invocation of “admiralty jurisdiction of the High Court of Kerala”, in Socratic sense we may have to define our terms at the threshold. What exactly is the scope and ambit of the term “admiralty jurisdiction”? We are readily assisted by the definition as laid down in Section 20 of the Supreme Court Act, 1981 (which is a statute of United Kingdom and has engaged the attention of the Learned Judge’s as revealed from para 19 of the Free Neptune Judgment). Sec.20 of the said Act states that Admiralty Jurisdiction of the High Court shall include the Jurisdiction to hear and determine any questions and claims mentioned in sub clause (2) of the Act. The said sub-clause (2) enumerates under (a) to (s) the questions and claims. Sub-clause 2 (e), (g) and (h) are of direct interest. (e) speaks of any claim for damage done by a ship, (g) any claim for loss or damage to goods carried in a ship, and (h) any claim arising out of any agreement relating to the carriage of goods in a ship or to the use or hire of a ship. [Sub clause (f) also would assume relevance depending on whether the term “Personal Injury” used therein is wide enough to take in an injury/loss suffered by a cargo owner due to damage or short landing of cargo. Let’s save if for another time].

This definition of Admiralty Jurisdiction of the High Court as laid down in Section 20 of the Supreme Court Act, 1981 is in pari materia with the definition of “Maritime claim” in the 1952 Brussels Convention on Arrest of Ships.

What follows is that since the Learned Judges have in Free Neptune laid down a law that hereinafter all motions invoking the ‘admiralty jurisdiction’ of the High Court of Kerala shall be civil suits, and since the term ‘admiralty jurisdiction’ as examined above herein above takes in ‘any claim for damage done by a ship’, ‘any claim for loss or damage to goods carried in a ship’, and ‘any claim arising out of any agreement relating to the carriage of goods in a ship or to the use or hire of a ship’, it may be open to file suits for realizing said claims before the Hon’ble High Court of Kerala invoking its admiralty jurisdiction. Strangely enough, small civil suits for such paltry sums as Rs.50,000/- which hitherto were filed in the Subordinate Judges Court, Cochin could possibly be filed before the Hon’ble High Court of Kerala invoking its admiralty jurisdiction. Whether it’s desirable that the Highest Court of the land, which since its inception has not handled civil suits and is insufficiently equipped (administratively) for handling prolonged civil trials involving complex maritime legal issues, should now commence adjudicating such cases is a question to be pondered on.

Moreover, is it necessary for the Hon’ble High Court to relegate to itself all suits involving maritime claims? Even more so since all suits pertaining to maritime claims need not necessarily contain a relief for arresting a foreign vessel and could simply be a suit for money arising out of a carriage of goods by sea contract. Thus all maritime claims need not lead to invocation of admiralty jurisdiction in the sense of arresting the defaulting ship. Such maritime claims which are pure and simple civil suits could as well be adjudicated by the Subordinate Judge’s Court as is presently being done, the said courts being well equipped to deal with such complex questions requiring appreciation of evidence in detail.

Another equally interesting situation looms large due to the said laying down of law in Free Neptune. It relates to Sec. 443 of the Merchant Shipping Act, 1958. The said provision too has engaged the attention of the learned Judges while rendering Free Neptune Judgment as can be revealed from para 20. Sec. 443 speaks about detention of a foreign vessel while within Indian Jurisdiction. The difference between ‘Arrest’ and ‘Detention’ of a ship assumes significance here. Arrest practically and theoretically is graver than Detention. Detention is a condition which the ship endures more than frequently during her life. It is less rigorous from Arrest, both in cause and effect. A detailed exposition of the difference may be out of place here, suffice to say in the context of Sec.443 that the term Arrest has been purposefully excluded by the Legislature in Secs. 443 and 444 of the Act. Instead it only speaks of detention. A co-joint reading of the said two sections will reveal that power of detention exists both in the High Court as well as on an officer of the port (albeit temporarily). Thus detention is a power evidently different from Arrest which as is said to exist only in the Highest Courts of Record having plenary power. An officer of the port may not be able to arrest a ship though he could detain it on various grounds one of which could be as explained in Sec.443 (2). The Hon’ble Supreme Court also while discussing powers under 443 and 444 termed them as merely procedural and substantive rights like that of Arrest lies else where. Coming back again to Free Neptune judgment lets examine how the dictum therein that civil suits alone could be filed invoking admiralty action, impact Secs. 443 and 444 of Merchant Shipping Act, 1958? A motion under Sec.443 to the High Court will have all the draping of and resemblances to a ‘maritime claim’ and to an ‘admiralty action’. It will for sure involve a foreign ship which might have caused damage to or loss to the cargo of an Indian citizen and the claim could lead to a claim over the vessel herself. Sec. 443 does not state that a civil suit has to be preferred for invoking the procedure laid down therein. If he moves the High Court purporting to invoke 443 he ought not be compelled to file a civil suit stating that his motion has all draping of invocation of admiralty jurisdiction. By all means the procedure laid down under Sec.443 for moving the High Court was a special jurisdiction conferred on the High Court. It was made part of the statute in 1958, at a time when admiralty jurisdiction and arrest was being exercised by the chartered High Courts in India. It was thus a procedural right available to an Indian Citizen against a foreign ship in addition to the right of arrest which he may have had under general law. The nomenclature Special Jurisdiction Case (Sp.J.C.) hitherto followed by the Registry of the High Court of Kerala while numbering motions made under Sec. 443 was thus apt and correct. The right vested in an Indian Citizen under Sec.443 of the Act to seek detention (not arrest) by moving the High Court will be effectively curtailed if his remedy to seek enforcement thereof could be invoked only by way of filing a civil suit as now seen laid down in Free Neptune. The situation will be even direr if the officer contemplated under Sec. 443 (2) refuses to exercise his power to detain the vessel notwithstanding existence of all prerequisites for such detention and a motion seeking mandamus is resisted contending that only suit is maintainable in the facts of the case. In effect, does the Judgment in Free Neptune exclude from its ambit motions under Sec.443? Can a writ or a Sp.J.C still lie to the High Court under Sec.443? The problems arising from the interplay of the provisions of the Merchant Shipping Act conferring jurisdiction on the High Court and the inherent powers of the High Court can be well gauged from the decision in Shipping Fund Development Committee v. M.V. Charisma [AIR 1981 BOMBAY 42].

In Free Neptune, after thus laying down the procedure to be followed for invoking the admiralty jurisdiction, the Hon’ble Court proceeded to lay down the law applicable till proper Rules are framed by the High Court. “We also declare that Rules framed by the Madras High Court in so far as they are not inconsistent with any other provision of law for the time being in force and with appropriate modifications shall apply to the conduct of such suits until this Court modifies the said Rules or the legislature intervenes in this regard.”

The choice of the Madras Rules as applicable during the interregnum was explained by the Hon’ble Court as follows: “ We make such a declaration not only because we owe an obligation under law to devise a procedure for the regulations of the proceedings before this Court as was pointed out by the Supreme Court in Elisabeth’s case at para 64… but also for the reason that a part of the territory over which this High Court now exercise jurisdiction was within the territorial jurisdiction of the Madras High Court prior to the States Reorganization Act, 1956. Therefore, for at least that part of the territory of the State of Kerala, which was within the jurisdiction of the Madras High Court prior to the States Reorganization Act, 1956 was governed by the law administered by the Madras High Court which devolved upon this Court by virtue of the operation of Section 52 of the States Reorganization Act, 1956.”

Since the Hon’ble Court was involved in the very crucial exercise of devising a procedure for the regulations of the proceedings before itself, a closer scrutiny would have been desirable. Cue could have been taken from the detailed exposition regarding similar question of admiralty jurisdiction of Orissa High Court in Reena Padhi v. Owners of Motor Vessel Jagdhir [AIR 1982 Orissa 57].

Moreover the reliance placed on and interpretation given to Sec. 52 of the States Reorganization Act, 1956 to justify the adoption of Madras Rules is not free from doubt. Erstwhile Malabar district which was an administrative district of former Madras Presidency is now part of Kerala state. But all along the west coast of India including over the erstwhile Malabar district, High Court of Bombay as a colonial court of admiralty had exercised admiralty jurisdiction especially since the old chartered high courts has been exercising overlapping admiralty jurisdiction. Even offlate the High Court of Bombay has been arresting ships berthed in Chennai. Since the law as applicable along the west coast including Malabar and the entire coast of Kerala, was the admiralty law as enforced by the High Court of Bombay, the more appropriate course of action to be adopted during the interregnum would have been to apply the Admiralty Rules of Bombay as it was ‘the law in force’ over that part of the state of Kerala ‘immediately before the appointed day’ as envisaged Sec. 52 of the States Reorganization Act, 1956.

Arrest of a vessel invoking admiralty jurisdiction is an action in rem. It is an action against a res or a thing and against unascertained persons, i.e., against the world at large, thus binding any one who has a real and subsisting interest in the res. All that is necessary is to retain the power of the High Court to entertain an action in rem thus retaining the power of the High Court to entertain an arrest motion under admiralty jurisdiction and to structure and refine its exercise. It is desirable that the inherent admiralty jurisdiction of the High Court in a motion in rem is confined to arrest of the relevant vessel found within its jurisdiction and upon furnishing of security by the person interested in the vessel, the action in rem thus being converted to an action in personam, the parties ought to be relegated back to the appropriate forum to fight out their action in personam by way of a suit or arbitration during the pendancy of which the security furnished should be kept alive. The system in place in High Court of Kerala before the Free Neptune judgment had effectively ensured the above. The principal draw back was that there was no sufficient safeguard against frivolous invocation of admiralty jurisdiction and consequent arrest of ships. The situation has to be remedied first by ensuring that no arrests orders are made by the High Court of vessels berthed beyond its territorial limits.

The need for retaining a special jurisdiction as Admiralty Jurisdiction is itself debatable. However, accepting the peculiar nature of maritime transactions and assuming that there is a need for treating them separately (see Sec. 112 of the CPC), are there any compelling reasons for the highest court of the state, already over burdened with litigations, to proceed to consider civil suits involving complex commercial questions of maritime law and facts which would require elaborate appreciation of evidence.

The judgment in Free Neptune case points out to the urgent need for a comprehensive legislation regarding admiralty law in India. It can be reasonably discerned from the slow death of the Admiralty Bill, 2005 that such a wait could be a fairly long one. Till then the only solution to the impasse appears to be adoption of comprehensive Admiralty Rules by the High Court of Kerala. The Admiralty Rules in force in Madras, Bombay or Calcutta have all become thoroughly outdated and needs fine tuning to meet the felt necessities of time and trade. A verbatim adoption or transplanting of any of such Rules as the Rules for the High Court of Kerala would only complicate things further since the very character of the said courts and the Kerala High Court are different. Being the only International Transshipment Terminal in India undertaking maritime activity of a unique nature, let’s hope that the Admiralty Rules to be evolved by the High Court would take note of the felt necessities of international trade as pointed out by the Supreme Court in MV Elizabeth case and noted with approval by the Hon’ble High Court of Kerala in the case of Free Neptune.

* * *

4 comments:

Dear sir,

Your Blog is really very informative.

i have too started a blog dedicated to Life At Sea.

but i am just an amatuare blogger your view on om blog will help me to improve the same.

regards

Nandkishore Gitte.

http://mylifeatsea.blogspot.com

WHAT A JOKE.

I also practice law at Kochi but as far as my knowledge goes ships are detained by filing of a writ petition and are not arrested under admiralty jurisdiction.

Since Kochi does not have Admiralty jurisdiction Kochi court till date have not passed any order of arrest of a vessel under Admiralty jurisdiction

Thanks for your scrutiny of Admiralty Jurisdiction at Kochi. Shedding your vast knowledge on arrest of vessels has led us to believe that you have commendable knowledge and understanding in maritime law. I would for that reason request you to enlighten us in this regard and thereby seek to justify your comment herein above, if it may please you...SIR.

Post a Comment